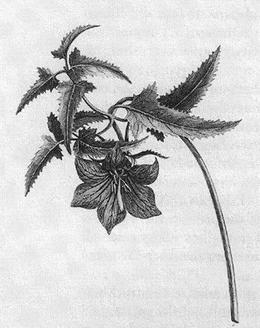

Truth-to-natureObjectivity in science appeared in the mid-nineteenth century. In the early eighteenth century, before objectivity, there existed an epistemic virtue in science which Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have called truth-to-nature. This ideal was practiced by Enlightenment naturalists and scientific atlas-makers and involved active attempts to eliminate any idiosyncrasies in their representations of nature in order to create images thought best to represent “what truly is.” Judgment and skill were deemed necessary in order to determine the “typical,” “characteristic,” “ideal” or “average.” In practicing truth-to-nature naturalists did not seek to depict exactly what was seen; rather, they sought a reasoned image.

|

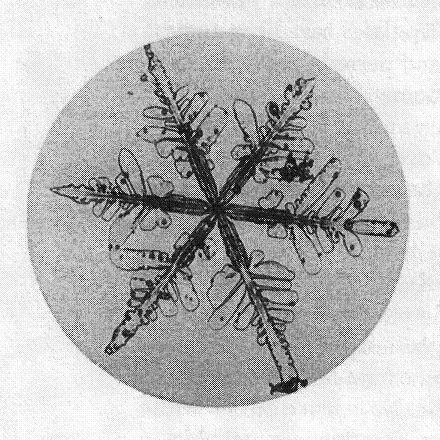

Mechanical objectivityIn the latter half of the nineteenth century objectivity in science was born when a new practice of mechanical objectivity appeared. “‘Let nature speak for itself’ became the watchword of a new brand of scientific objectivity.” It was at this time that idealized representations of nature, which were previously seen as a virtue, were now seen as a vice. Scientists began to see it as their duty to actively restrain themselves from imposing their own projections onto nature. The aim was to liberate representations of nature from subjective, human interference and in order to achieve this scientists began using self-registering instruments, cameras, wax molds and other technological devices.

|

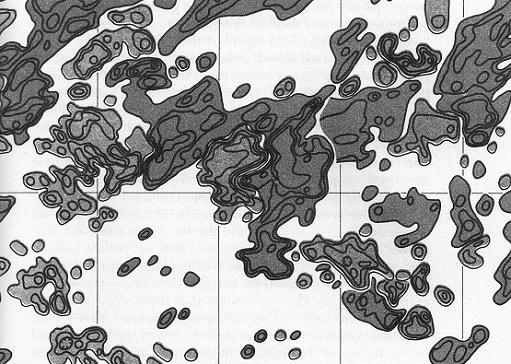

Trained judgmentIn the twentieth century trained judgment supplemented mechanical objectivity as scientists began to recognize that, in order for images or data to be of any use, scientists needed to be able to see scientifically; that is, to interpret images or data and identify and group them according to particular professional training, rather than to simply depict them mechanically. Objectivity now came to involve a combination of trained judgment and mechanical objectivity.

|